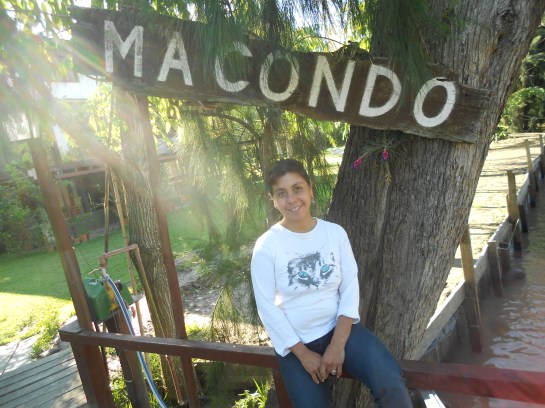

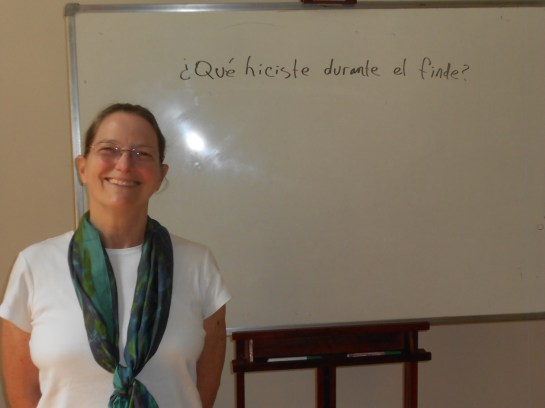

We had heard about the beaches of Uruguay for a while, and we wanted to see them, and to be on them, before heading south into Southern Argentina. More than anything, we wanted a break from the big city, a place and time where we could just sit and relax and reflect. Our Spanish teacher Nancy told us about a place in Uruguay called Cabo Polonio. From Buenos Aires, you take a ferry across the Río de la Plata to Montevideo, then you can travel by bus up the coast. She said that it was near the Brazilian border, that it was very simple and basic, small and quiet, and a “hippie place.” That was enough for us. We googled it, got in email contact with a place called Posada Cañada, and reserved a room.

We had heard about the beaches of Uruguay for a while, and we wanted to see them, and to be on them, before heading south into Southern Argentina. More than anything, we wanted a break from the big city, a place and time where we could just sit and relax and reflect. Our Spanish teacher Nancy told us about a place in Uruguay called Cabo Polonio. From Buenos Aires, you take a ferry across the Río de la Plata to Montevideo, then you can travel by bus up the coast. She said that it was near the Brazilian border, that it was very simple and basic, small and quiet, and a “hippie place.” That was enough for us. We googled it, got in email contact with a place called Posada Cañada, and reserved a room.

We left Buenos Aires on the 8:00 am ferry, and got to Montevideo at 11:00, then took a bus to a small beach town called Piriápolis, where we spent two nights at a small home that rents out rooms.

The beach was right down the road from our room, and we appreciated the message waiting for us there. Turn off your TV, Turn on your mind.

After a couple of days in Piriápolis, we headed for Cabo Polonio. First, we took a local bus to another small town, called Pan de Azúcar, then another bus for three hours. The bus drops you off on the highway, then you climb onto a four-wheel drive truck to drive you over the dunes into Cabo Polonio.

After a couple of days in Piriápolis, we headed for Cabo Polonio. First, we took a local bus to another small town, called Pan de Azúcar, then another bus for three hours. The bus drops you off on the highway, then you climb onto a four-wheel drive truck to drive you over the dunes into Cabo Polonio.

¡¡¡CABO POLONIO IS AWESOME AND TREMENDOUS!!!

¡¡¡CABO POLONIO IS AWESOME AND TREMENDOUS!!!

Cabo Polonio is a national park. There are no cars. The only electricity is solar and wind powered. There are people living there, but there is a moratorium on new building. No more. In the summer, (December, January, and February) it explodes with people from Montevideo and Buenos Aires. In the winter, it´s a town of fifty four people.

We stayed in a little posada, a half-hour walk from town down the beach. Nancy and Marco built the place and they were our hosts, along with their two sons, Luka and Tato, aged five and seven. The truck dropped us off in front of La Cañada, (canñada means springs, and there are two fresh water springs that flow around their house.) and Nancy came out to greet us with a kiss. She gave us a choice of two room, la grande or la chiquita, then opened up a bottle of beer for us to welcome us.

She gave us a choice of two room, la grande or la chiquita, then opened up a bottle of beer for us to welcome us.  Posada and Parador means that there are rooms to rent as well as meals to buy. Comidas Caseras means “homemade meals.” They have room for about twenty people when they are full, and it is easy to imagine people from all over the world spending a delightful afternoon on the porch.

Posada and Parador means that there are rooms to rent as well as meals to buy. Comidas Caseras means “homemade meals.” They have room for about twenty people when they are full, and it is easy to imagine people from all over the world spending a delightful afternoon on the porch.

Nancy put out some appetizers (picadas) for us, and gave us a great welcome. Very soon, Marco came home with the boys, after picking them up from school. He immediately rolled a joint to share with us. We decided to stay two more nights.

Nancy put out some appetizers (picadas) for us, and gave us a great welcome. Very soon, Marco came home with the boys, after picking them up from school. He immediately rolled a joint to share with us. We decided to stay two more nights.

We stayed for seven nights in all. The cost of the room (about forty dollars a night) apparently included all the porros that we wanted. La Cañada is beautiful. It is right on the beach, hand-made, colorful, with Nancy´s warm loving spirit infusing everything.  We became part of the family pretty quickly. We were the only guests, and we helped out in the kitchen and swept the floors, and had a great time with everyone. Monica liked to play cards with the kids, outside on the porch.

We became part of the family pretty quickly. We were the only guests, and we helped out in the kitchen and swept the floors, and had a great time with everyone. Monica liked to play cards with the kids, outside on the porch.  Soon after Marco arrived with the kids, they went down to the beach for a swim. Beautiful sunny weather. Monica and I followed them to the beach, waved to them, and walked down the beach. You can walk for at least twenty kilometers down the isolated beach before running into anybody. The next day, Luka, who is seven, looked at me very seriously and asked me why we hadn´t gone swimming with them yesterday. (This in perfect Spanish. They learn Spanish so young down here.) I was touched and taken aback. Up to that point, thekids hadn´t really communicated much with us. I told Luka that we didn´t swim because we wanted to take a walk, but if they go swimming this afternoon, I´ll go with them. He answered, “Bien.” So, later that afternoon, I joined them in the water, swimming and surfing, while Marco was the lifeguard and Nancy watched from a beach chair. After that, we were best friends with the boys.

Soon after Marco arrived with the kids, they went down to the beach for a swim. Beautiful sunny weather. Monica and I followed them to the beach, waved to them, and walked down the beach. You can walk for at least twenty kilometers down the isolated beach before running into anybody. The next day, Luka, who is seven, looked at me very seriously and asked me why we hadn´t gone swimming with them yesterday. (This in perfect Spanish. They learn Spanish so young down here.) I was touched and taken aback. Up to that point, thekids hadn´t really communicated much with us. I told Luka that we didn´t swim because we wanted to take a walk, but if they go swimming this afternoon, I´ll go with them. He answered, “Bien.” So, later that afternoon, I joined them in the water, swimming and surfing, while Marco was the lifeguard and Nancy watched from a beach chair. After that, we were best friends with the boys.

They go to school in town. There are a total of six students at the school, with Tato and Luka being two of them. All the school kids in Uruguay and Argentina wear smocks (guardapolvos) to school. Luka and Tato usually got driven down the beach in the pickup truck and then got picked up in the afternoon. Here, they are ready for school.  School is usually from about 10:00 to 2:00, but it depends on the bus schedules and the teacher´s schedule. She lives about 30 km from town, and she travels by bus to get there and go home.

School is usually from about 10:00 to 2:00, but it depends on the bus schedules and the teacher´s schedule. She lives about 30 km from town, and she travels by bus to get there and go home.

Nancy and Marco are both great cooks, and they both put their heart into preparing food for their guests. Breakfast was always cheerful, with coffee and a chapati, (kind of a grilled quesadilla) They put a lot of effort into dinner, which was usually served around 10:00 at night. They have a beautiful parilla for grilling meat, and a beautiful brick oven for baking breads and pizzas. Nancy kneads all the dough. In the summer, when they are full with guests, Marco can fill the parilla with enough meat for twenty people, at the same time baking pizzas in the oven.  The oven is made with bricks and covered with mud. It holds the heat. It is solid. They built the parilla and the oven before they built the rest of the house. I appreciate their priorities.

The oven is made with bricks and covered with mud. It holds the heat. It is solid. They built the parilla and the oven before they built the rest of the house. I appreciate their priorities.  One night, Nancy de-boned a chicken, sliced it thin and rolled it out, and filled it with prunes and cheese, ham and spices, then stuffed it into a plastic water bottle, then put a baking net over the bottle, and slipped the bottle out. They baked the chicken for three hours. Delicious. I told Nancy and Marco that I´ll do it in Oregon and call it Pollo Cañada.

One night, Nancy de-boned a chicken, sliced it thin and rolled it out, and filled it with prunes and cheese, ham and spices, then stuffed it into a plastic water bottle, then put a baking net over the bottle, and slipped the bottle out. They baked the chicken for three hours. Delicious. I told Nancy and Marco that I´ll do it in Oregon and call it Pollo Cañada. I asked if I could knead the dough for pizza and bread one night, and it was very nice being part of the production instead of just being served. I loved their kitchen, with that big marble work table in the middle. I was very impressed with how much food they are able to turn out, and all with such love and cheer.

I asked if I could knead the dough for pizza and bread one night, and it was very nice being part of the production instead of just being served. I loved their kitchen, with that big marble work table in the middle. I was very impressed with how much food they are able to turn out, and all with such love and cheer.  We arrived on a Tuesday (election day). On Friday afternoon, after days of sunshine, the sky turned black and the clouds moved in, and we had a real storm. Lighting over the ocean, strong wind, heavy rain. The rain stopped during the night, but the wind blew for three days. It was more than a gale. The ocean kicked up, and the wind was powerful. It stayed that way until the day we left. On Friday, besides the storm, three other guests also arrived. Gabriel and Florencia were a young couple, he from Montevideo and she from Buenos Aires, and Frederic was from Paris. Frederic had already been traveling for two years, following a spiritual path, with stops in monasteries and with Thich Nhat Hanh. Gabriel and Florencia loved to sing. The day after the storm, with the fierce wind blowing and the ocean riled up and rollicking, Flor gently played the guitar and the two of them sang and filled the house with music all day long.

We arrived on a Tuesday (election day). On Friday afternoon, after days of sunshine, the sky turned black and the clouds moved in, and we had a real storm. Lighting over the ocean, strong wind, heavy rain. The rain stopped during the night, but the wind blew for three days. It was more than a gale. The ocean kicked up, and the wind was powerful. It stayed that way until the day we left. On Friday, besides the storm, three other guests also arrived. Gabriel and Florencia were a young couple, he from Montevideo and she from Buenos Aires, and Frederic was from Paris. Frederic had already been traveling for two years, following a spiritual path, with stops in monasteries and with Thich Nhat Hanh. Gabriel and Florencia loved to sing. The day after the storm, with the fierce wind blowing and the ocean riled up and rollicking, Flor gently played the guitar and the two of them sang and filled the house with music all day long.  We walked into Cabo Polonio a few times during our stay. The main part of the town is the lighthouse. There are beautiful little homes there also, and at the base of the lighthouse, there is a colony of lobos marinos (sea lions). There are no cars here. The people arrive by the big trucks, as well as the supplies for the restaurants and hostels. The restaurants use gas tanks for cooling and freezing, and most of them have solar and wind power for lights. At night, looking at the town from a distance, the only thing you see is the lighthouse.

We walked into Cabo Polonio a few times during our stay. The main part of the town is the lighthouse. There are beautiful little homes there also, and at the base of the lighthouse, there is a colony of lobos marinos (sea lions). There are no cars here. The people arrive by the big trucks, as well as the supplies for the restaurants and hostels. The restaurants use gas tanks for cooling and freezing, and most of them have solar and wind power for lights. At night, looking at the town from a distance, the only thing you see is the lighthouse.

Along the beach, there are also some houses, although they were empty. I think that once the summertime hits, there will be people here.

Along the beach, there are also some houses, although they were empty. I think that once the summertime hits, there will be people here.

This next one always reminded me of Robinson Crusoe.

This next one always reminded me of Robinson Crusoe.

We loved our week at Cabo Polonio. It was very sad to say goodbye to the family, and we hope to keep in touch. Uruguay has been great. Now we look forward to new places.

We loved our week at Cabo Polonio. It was very sad to say goodbye to the family, and we hope to keep in touch. Uruguay has been great. Now we look forward to new places.

But undoubtedly our most memorable experience was making friends with Paz and Lucrecia who staffed the museum of natural history. It was they who sent us adventuring to the fossil beds and lighthouse, and we visited them almost every day at the museum, sharing mate and English lessons. We miss them already.

But undoubtedly our most memorable experience was making friends with Paz and Lucrecia who staffed the museum of natural history. It was they who sent us adventuring to the fossil beds and lighthouse, and we visited them almost every day at the museum, sharing mate and English lessons. We miss them already.