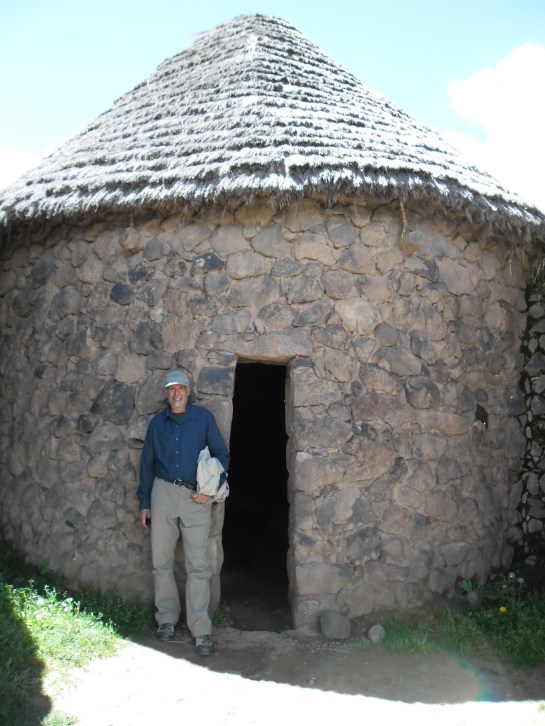

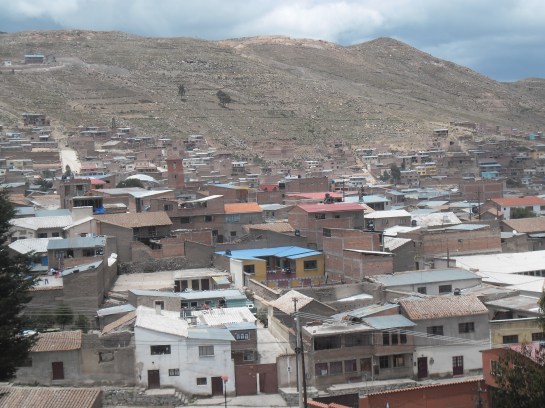

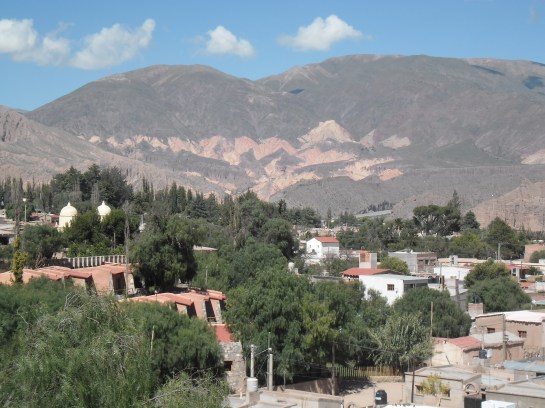

Cusco is the most tourist-visited city in South America. There are lots of reasons. It is in the very heart of the Andes Mountains, and the Andes are magnificent. The Andes extend more than 5000 kilometers, from Venezuela in the north down through Chile and Argentina in the south, with peaks higher than 20,000 feet. The town of Cusco sits in a basin at 11,150 feet in elevation. It is surrounded by higher mountains. They’re green. We are still in the tropics. Cusco was the capital and center of the splendid Inca civilization, which was in its prime seven hundred years ago. Downtown Cusco today is full of Incan architecture, still standing and still strong. The stunning, mesmerizing, incredible aspect of the architecture is the Incan stonework. They used rocks and stones and boulders, many of them weighing tons, to build temples and homes and fortresses. They carved and sculpted and shped each rock to fit perfectly (perfectly!) with the surrounding rocks No mortar. No cement. Just a perfect (perfect!) fit, with the rocks leaning into each other to support each other. The classic comment is that you cannot fit a credit card between the stones, but you can’t stick a needle in there either.

This particular stone is the most famous one in Cusco. It is called “The 12-angled stone.” The workmanship to fit it into the wall is quite impressive.

This rockwork is one of the great mysteries of the world. How did they do it? How did they transport the rocks over the great distances? How did they lift the rocks up twenty or thirty feet? How did they fit them so perfectly? And how did they make their buildings so seismographically sound, strong enough to withstand the severe earthquakes that hit here? Seismologists from North America, Asia, and Europe have come to Cusco over the years to study the architecture. Some of these scientists have concluded that the only possible explanation for the accuracy of the cutsis that the Incas used laser beams. Another popular theory concerns the intervention of extraterrestrials. The only thing that we really know for sure is that, today, with our technology, we couldn’t duplicate these structures.

Anyway, people come to Cusco to see these stone walls. And they come for the mountains. And forthe Inca ruins onthe outskirts and all around Cusco. And, of course, for Machu Picchu, one of the seven wonders of the world. But that’s another day.

We spent eight days in Cusco. Monicatook Spanish classes Monday through Friday, from 9:00 in the morning until 1:00 p.m. She made some good progress in conversation skill, and also in using the subjunctive mood, both the present and future, as well as the imperfect subjunctive! (this is for the benefit of fellow language nerds out there.) Moni’s teacher was a woman named Magda (short for Magdalena). It was a one-on-one class,and they talked about lots of things.One day, they went to the public market and talked about, among other things, the hundreds of different types of potatoes that are grown in The Sacred Valley.

I (Mike) used my time to wander around the city a bit, and to sit in the plaza. The city is full of narrow streets, and stairs to go up and down.

The Peru flag is on the left. The Cusco flag is on the right. The rainbow flag flies over all the government buildings.

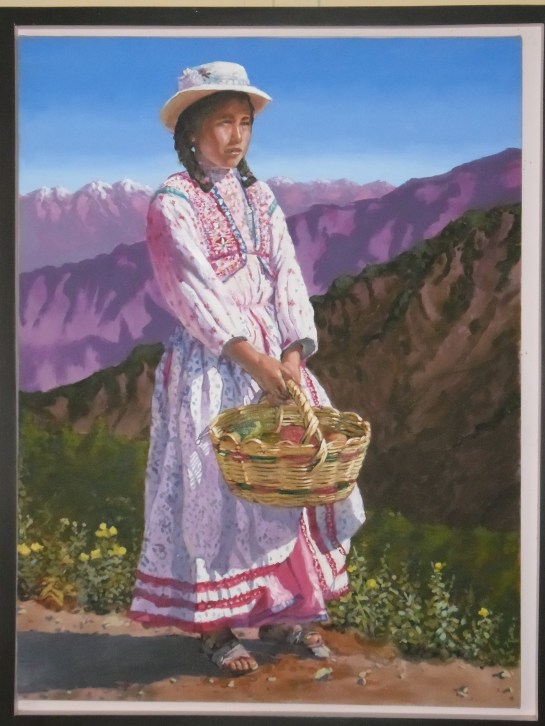

Cusco is vibrant. It is a mix of ancient and modern. Colonial and indigenous. There are people here from all over the world. There is a mix of cultures and an acceptance. Good restaurants. Good coffee. The local people talk to the tourists. This can be good and bad. On the one hand, it’s easy to meet and talk to people. On the other hand, there are seemingly thousands of people out on the street who are hoping to sell you something. Guys with paintings, women with jewelry or weavings or sculpted gourds. They see you and come after you. “Looking is free.” “Please buy something from me.” “I make you a good price.” “Look how beautiful.” If you sit on a bench in the main square, you will be approached. Some of the vendors can get quite insistent. Sometimes it can get a little infuriating. We bought some things, and a few times, we just gave some money without buying anything. It’s all such a delicate balance.

Cusco is vibrant. It is a mix of ancient and modern. Colonial and indigenous. There are people here from all over the world. There is a mix of cultures and an acceptance. Good restaurants. Good coffee. The local people talk to the tourists. This can be good and bad. On the one hand, it’s easy to meet and talk to people. On the other hand, there are seemingly thousands of people out on the street who are hoping to sell you something. Guys with paintings, women with jewelry or weavings or sculpted gourds. They see you and come after you. “Looking is free.” “Please buy something from me.” “I make you a good price.” “Look how beautiful.” If you sit on a bench in the main square, you will be approached. Some of the vendors can get quite insistent. Sometimes it can get a little infuriating. We bought some things, and a few times, we just gave some money without buying anything. It’s all such a delicate balance.

It is a treat sometimes to talk to and get to know the artists. One day I was sitting in a small plaza, Plaza San Blas, and there was an indigenous woman sitting there also, spinning wool with a drop spindle, then weaving with it. I talked with her for a half-hour before buying a beautiful thin wall hanging from her. Spinning and weaving with alpaca wool is a centuries-old art and skill. I watched Felipa as she horizontally placed one thread at a time through the vertical threads (she said that there were 84 threads) to produce designs of, among other things, pumas, hummingbirds, llamas, owls, condors, and even a depiction of Tupac Amaru, an indigenous leader, being torn apart by four horses. (You gotta love the Spaniards.)

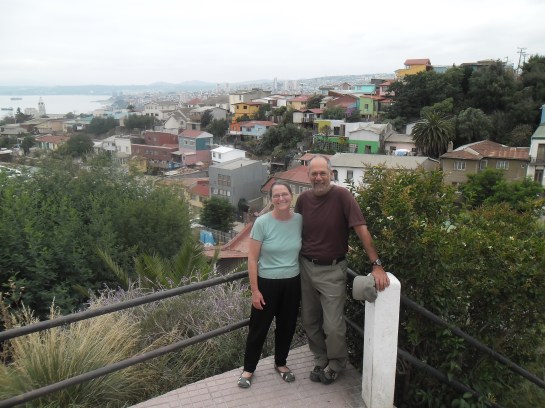

Monica bought a bracelet from a woman named Maruca. Maruca sets up shop on some steps that lead up to a mirador. We talked with her for a long time, and Monica watched as she macramed a few beautiful bracelets.

One day, a chica named Jovana pulled us into her little shop and giggled as she dressed us up in traditional clothing. She had a great time doing it, all because Monica wanted to buy a stuffed guinea pig (called cuy) that was in front of her store. Cuy is kind of a national dish here. Lots of restaurants serve it, oven roasted. Cusco has something for everyone. We loved getting to know the city and some of the people. The heart of the Andes. The heart of the cusqueños.