We spent last weekend out on the Delta, with Susana and Julio. They have a home on the Parana Delta, which is outside of the town of Tigre, about an hour’s train ride from Buenos Aires. The delta is a huge system of water and islands, formed as the Río Paraná fans out and interweaves before joining the Río de la Plata. There are thousands of little islands, and thousands of people living on the delta, and they are reached only by boat. The “lanchas” leave and return to Tigre, which is the home base for all the island people.

Susana and Julio built their own home on a piece of land that they bought after the economic crisis of 2001. Some of their friends went to Brazil. Some of them went to Spain. They decided that this would be a good time to try to achieve their dream. A time of crisis can also be one of opportunity, and they slowly started to build their home. Julio said that when you don’t have anything to lose, it’s easier to take a risk.

The boats are the life of the delta.They depart from Tigre every few hours, and different boats follow different routes. Some travel up this river, some travel up that river. Susana and Julio live on the Caraguata River. We bought our tickets, then it was a little confusing knowing which boat to get on. There were about four boats being loaded with people and gear. We told the boatman (el lanchero) that we were going to Caraguata, and he showed us which boat to get on.

We got on, found a seat and sat down, and soon we were on our way. There was room for about thirty people on the boat, and there were about twenty. There were banks of seats along the windows, and rows of seats facing forward. We sat along the window, and we could reach out and touch the water, the boat was so low on the water.

We got on, found a seat and sat down, and soon we were on our way. There was room for about thirty people on the boat, and there were about twenty. There were banks of seats along the windows, and rows of seats facing forward. We sat along the window, and we could reach out and touch the water, the boat was so low on the water.

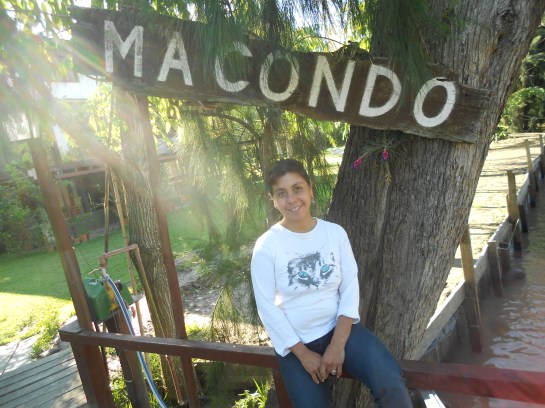

We motored away from Tigre, and soon veered off at a fork. Now we were on the Río Caraguata. I went up and asked the lanchero if he could notify us when we reached our destination, the island of Macondo. Julio named his little spot Macondo, because he had read One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Marquez, when Julio was a hippie selling bracelets on the beaches of Cartagena, Colombia in the 70’s. The water in the delta is cappuccino brown, but it is clean. It is full of minerals from the inland jungle. The Paraná is South America’s second longest river, after of course the Amazon. By the time it reaches the delta, it´s already gone over 2000 miles. It´s the only delta in the world that empties into fresh water, el río de la plata. The water system is huge, and each river is only a small part of it.

As we made our way up the river, we passed hundreds of docks. Usually we just kept going,but every now and then the boat would pull up to one, go into reverse and get right next to the dock, and somebody would jump off the boat, onto the dock, and they would be home. I wondered how the driver knew which docks to stop at. He didn’t have a list. Nobody called out to tell him. He just stopped, and somebody was home. I asked Julio and Susana about it, and they smiled and said that the driver knows who’s on board, and he knows where they live. Every home has its own name, and there are hundred and hundred of homes, each with a name and each with a dock.Pretty personal service.

Susana and Julio greeted us at the dock and welcomed us to their beautiful home.

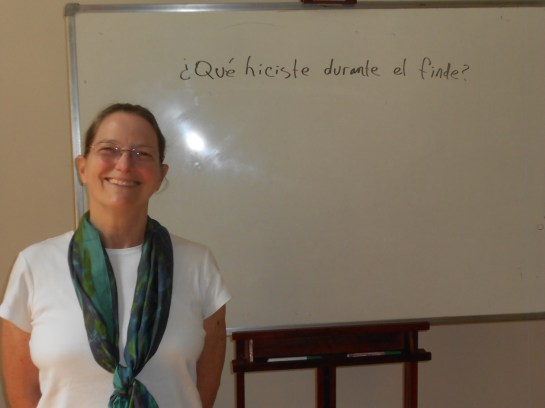

We looked at their photos of when they were building the house. It took them five years, bit by bit. All the building material had to come in by boat. When they were building it, there was no electricity. Julio did almost all the work by himself. Now they have a little piece of heaven, and they are happy as can be. They take in guests during the summer to supplement their income. (Susana is a professor) They are able to share a little bit of the Delta experience.

We looked at their photos of when they were building the house. It took them five years, bit by bit. All the building material had to come in by boat. When they were building it, there was no electricity. Julio did almost all the work by himself. Now they have a little piece of heaven, and they are happy as can be. They take in guests during the summer to supplement their income. (Susana is a professor) They are able to share a little bit of the Delta experience.

Soon, we heard a horn from out on the river. The “lancha almacen” was coming. This is the mobile store. It passes by, usually once a day, and it sells things that the people might need. A lot of coca-cola and beer, and also propane tanks, bottled water, canned goods, eggs and some produce. All you have to do is run down to the dock and wave to them. They’ll stop and bring you what you want. Susana was happy to see it coming.  We spent a peaceful afternoon sitting on the dock and watching the river. Boats would pass, coming and going. Lots of parrots.

We spent a peaceful afternoon sitting on the dock and watching the river. Boats would pass, coming and going. Lots of parrots.

We shared a pizza for dinner with our hosts, and spent a few hours talking. Lovely evening in the candlelight. Susana served us an elegant breakfast in the morning, and we relaxed and talked and lounged away a few hours until our boat came to take us back to Tigre.

We shared a pizza for dinner with our hosts, and spent a few hours talking. Lovely evening in the candlelight. Susana served us an elegant breakfast in the morning, and we relaxed and talked and lounged away a few hours until our boat came to take us back to Tigre.